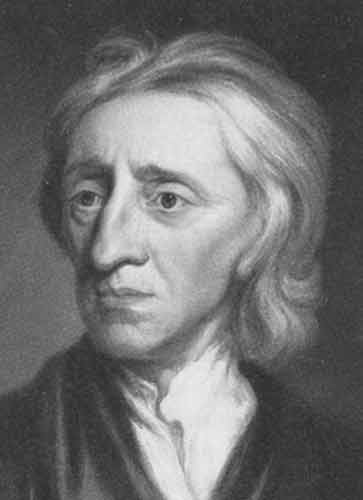

John Locke is the apostle of the revolution of 1688. Its aims were modest, but they were exactly achieved. Locke faithfully embodies its spirit. His most important book in theoretical philosophy is the Essay Concerning Human Understanding. He completed his book just at the moment when the government of his country fell into the hands of men who shared his political view. In his second book of the essay, Locke shows in detail how experience gives rise to various kinds of ideas. I think the following statement has a sense of truth, and the only way to increase our knowledge is through experience, he says:

“Let us then suppose the mind to be, as we say, white paper, void of all characters, without any ideas; how comes it to be furnished? Whence comes it by vast store, which the busy and boundless fancy of man has painted on it with almost endless variety? Whence has it all the materials of reason and knowledge? To this I answer in one word, from experience: in that all our knowledge is founded and from that it ultimately derives itself.”

Our ideas are derived from two sources, sensation and perception. Since we can only think by means of ideas, and since all ideas come from experience, it is evident that none of our knowledge can antedate experience.

Our ideas are derived from two sources, sensation and perception. Since we can only think by means of ideas, and since all ideas come from experience, it is evident that none of our knowledge can antedate experience. Perception, he says, is the first step and degree towards knowledge, and the inlet of all the materials of it. In modern day, this is commonsense, however in his day the mind was supposed to know all sorts of things and the complete dependence of knowledge upon perception, which he proclaimed, was a new revolutionary doctrine.

Locke wrote his two treatises on government. The first of these two treatises is a criticism of the doctrine of hereditary power. It is a reply to Sir Robert Filmer’s Patriarcha. The King according to Filmer, is perfectly free from all human control, and cannot be bound by acts of his predecessors, or even by his own, for impossible it is in nature that a man should give a law unto himself. Filmer belonged to the most extreme section of the Divine Right Party.

Patriarcha begins by combating the common opinion that mankind is naturally endowed and born with freedom from all subjection, and at liberty to choose what form of government it please, and the power which any one man has over others was first bestowed according to the discretion of the multitude.

Locke suggests if parental power is what is concerned; the mother’s power should be equal to the father’s. He lays stress pm the injustice of primogeniture which is unavoidable if inheritance is to be the basis of monarchy. Paternal power, he says, is temporary and extends not life or property. Hereditary cannot, according to Locke, be accepted as the basis of legitimate political power.

What I also found interesting when reading Locke is his state of nature and natural law. As Russell says some parts of Locke’s natural law are surprising. He gives the example; Locke says that captives in a just war are slaves by the law of nature. He says also that by nature every man has a right to punish attacks on himself or his property, even by death.

Locke’s idea of natural right is also very interesting. It is generally held that no man can be blamed for defending himself against a murderous assault, even, if necessary, to the extent of killing the assailant. He may equally defend his wife and children, or any member of the general public. In such case, the existence of the law becomes irrelevant, if, the man assaulted would be dead before the aid of the police could be invoked; we have to fall back on natural right. If you see a man making a murderous assault on your brother you have a right to kill him, if you cannot otherwise save your brother. In a state of nature Locke holds if a man has succeeded in killing your brother, you have a right to kill him. But where the law exists, you lose this right, which is taken over by the state. And if you kill in self-defence or in defence of another, you will have to prove to a law-court that this was the reason for the killing.

Descartes’ authority as a philosopher was enhanced, in his own day, by his work in mathematics and natural philosophy. But his doctrine of vortices was inferior to Newton’s law of gravitation as an explanation of the solar system. The victory of the Newtonian cosmogony diminished men’s respect for Descartes and increased their respect for England. Both these causes inclined men favourably towards Locke.

In the last times before the revolution, Locke’s influence in France was reinforced by that of Hume. In England, the philosophical followers of Locke, until the French Revolution, took no interest in his political doctrines. Berkley was a bishop not much interested in politics; Hume was a Tory who followed the lead of Bolingbroke.

What I found most interesting when reading John Locke’s Essay Concerning Human Understanding Chapter 1 of Ideas in general, and their Original, was Idea is the object of thinking. Locke suggests here that every man whilst thinking, has ideas in mind, but he asks the question where do these ideas come from. All ideas come from sensation or reflection suggests that experience and observation is where we get the knowledge and ideas we hold in our minds.

Locke states our senses convey into the mind several distinct perceptions of things, according to those various ways objects affect them. For example senses such as hot, cold, hard and soft are called sensation.

Perceptions such as thinking, doubting, believing and knowing are described by Locke as the different acts of our own minds which we observe in ourselves. He calls this reflection.

I also find Locke’s observable in children statement interesting. Locke says that at a child’s first coming into the world, we have little reason to believe he will be stored with knowledge and ideas that will be the matter of his future knowledge. This is true because, how do we know what a new born infant is thinking at birth, we hear it cry but we can’t hear its thoughts. Then when we do grow older we can’t remember our feelings or thoughts or anything we saw or heard the day we were born. Instead, Locke says, we come to be furnished with ideas and thoughts. As we grow older, we will start to gain our own ideas and experiences and from there we will start to store in our memory, our own understandings.

Well done - very good blog on Locke - and I think you're completely right to linger over Locke's concepts of natural rights and natural law. I'll be interested to hear what you make of Rousseau's "General Will" in this context when we discuss him in Semester II.

ReplyDeleteTry to find time to blog on the Winol bulletin too - www.winol.co.uk - it would be useful for the second and third years to hear your thoughts.